“Wilson Small,” July 10.

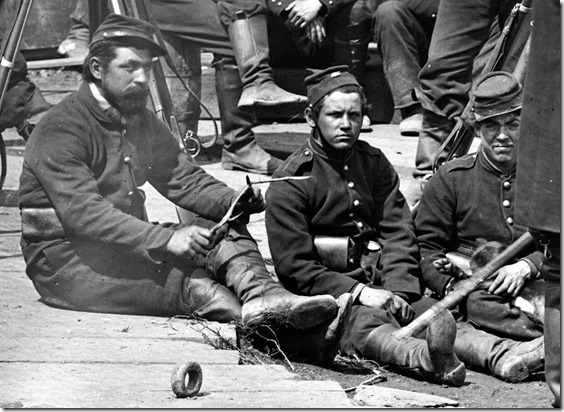

Dear A., — This morning I went ashore with Mrs. Barlow (Arabella, wife of the General) without orders and, indeed, without permission. But Mrs. Barlow offered to take me, Mr. Olmsted was not on board, and I was so anxious to see for myself the state of things that I could not forego the chance. The hospital occupies the Harrison House, called Berkley (how familiar all those names are to you and me!), and a barn, out-buildings, and several tents at the rear, containing, or I should say able to contain, in all, about twelve hundred men, — perhaps more, at a pinch. About a third of those now in hospital will be fit for duty after a week or two of rest.

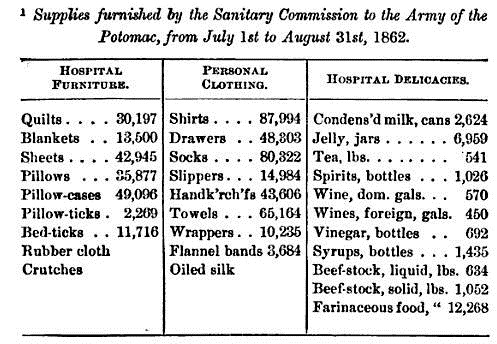

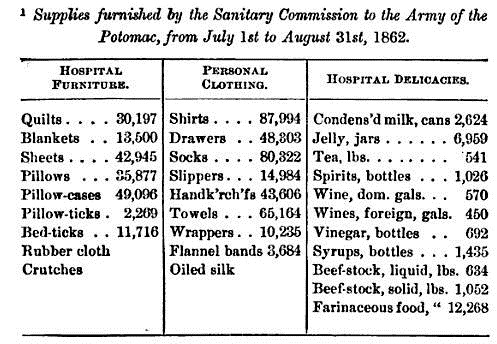

The influence of the new Medical Director is already manifest. It would be too much to say that all the wants of the sick and wounded are met as they would be on our own boats, where the men are as well cared for as in a city hospital, — it would be absurd to expect as much as that in a temporary hospital hastily arranged, and especially after such an exhausting march as the army has just made; but I am quite satisfied that the men have every essential care; the situation is the healthiest to be found about here, there are surgeons enough, and an excellent hospital-steward, with properly appointed ward-masters and nurses. I told the hospital-steward how much we depended on beef-stock and milk-punch, because they are so quickly and easily prepared; and I promised to send him (I felt as if I were making a will) my spirit-lamp and kettles, and to get our commissary to give him an ample supply of Muringer’s beef-extract, and condensed milk. I have just filled two pillow-cases for him with all the odds and ends that remain to me, — fans, pads, handkerchiefs, towels, bay-rum, cologne, bandages, flannel, pins, needles, tapes, buttons, paper and pens, etc., and ray precious lamp, with all its adjuncts.

We stayed about three hours with the men, writing letters for them. Such letters are often very funny. Some few told the horrors of the march; but as a rule they were all about the families at home. Did you ever notice how people of limited education seem unable to relate anything that is happening about them? They go over a string of family details quite as well known to their correspondent as to themselves.

I am glad I went ashore, for now I am quite content to go home. Our work — I mean the women’s work — is over, except on the ” Webster” and the “Spaulding,” which must still make two or three trips in the service of the Commission. All that now remains to be done for the army on the James is the regular work of inspecting camps and issuing from the store-boats such supplies as may be needed. [1]

I did not go on board the “Monitor” on “Wednesday, after all. The others went, but I had fallen into a weary and disconsolate condition, in which the effort seemed too great. Commodore Rodgers had tried to keep the President, who paid him an early visit, long enough to meet us; but Mr. Lincoln said: “No, he had promised to be with Georgy at nine o’clock, and Georgy must not be kept waiting.” I liked the story; it seemed to picture such happy relations between the President and the General.

[1]

On Mr. Olmsted’s return from Harrison’s Landing he sent down, as the most pressing need of the army (the shadow of scurvy was hanging over it) a vessel freighted with vegetables. A cargo of ice had preceded it. These vegetables proved of invaluable service, and were distributed to all the regiments at Harrison’s Landing.