JULY 7TH.—Gen. Huger has been relieved of his command. He retains his rank and pay as major-general “of ordnance.”

Gen. Pope, Yankee, has been assigned to the command of the army of invasion in Northern Virginia, and Gen. Halleck has been made commanding general, to reside in Washington. Good! The Yankees are disgracing McClellan, the best general they have.

Saturday, July 7, 2012

July 7th.

As we have no longer a minister — Mr. Gierlow having gone to Europe — and no papers, I am in danger of forgetting the days of the week, as well as those of the month; but I am positive that yesterday was Sunday because I heard the Sunday-School bells, and Friday I am sure was the Fourth, because I heard the national salute fired. I must remember that to find my dates by.

Well, last night being Sunday, a son of Captain Hooper, who died in the Fort Jackson fight, having just come from New Orleans, stopped here on his way to Jackson, to tell us the news, or rather to see Charlie, and told us afterwards. He says a boat from Mobile reached the city Saturday evening, and the captain told Mr. La Noue that he brought an extra from the former place, containing news of McClellan’s surrender with his entire army, his being mortally wounded, and the instant departure of a French, and English, man-of-war, from Hampton Roads, with the news. That revived my spirits considerably — all except McClellan’s being wounded; I could dispense with that. But if it were true, and if peace would follow, and the boys come home —! Oh, what bliss! I would die of joy as rapidly as I am pining away with suspense now, I am afraid!

About ten o’clock, as we came up, mother went to the window in the entry to tell the news to Mrs. Day, and while speaking, saw a man creeping by under the window, in the narrow little alley on the side of the house, evidently listening, for he had previously been standing in the shadow of a tree, and left the street to be nearer. When mother ran to give the alarm to Charlie, I looked down, and there the man was, looking up, as I could dimly see, for he crouched down in the shadow of the fence. Presently, stooping still, he ran fast towards the front of the house, making quite a noise in the long tangled grass. When he got near the pepper-bush, he drew himself up to his full height, paused a moment as though listening, and then walked quietly towards the front gate. By that time Charlie reached the front gallery above, and called to him, asking what he wanted. Without answering the man walked steadily out, closed the gate deliberately; then, suddenly remembering drunkenness would be the best excuse, gave a lurch towards the house, walked off perfectly straight in the moonlight, until seeing Dr. Day fastening his gate, he reeled again.

That man was not drunk! Drunken men cannot run crouching, do not shut gates carefully after them, would have no inclination to creep in a dim little alley merely to creep out again. It may have been one of our detectives. Standing in the full moonlight, which was very bright, he certainly looked like a gentleman, for he was dressed in a handsome suit of black. He was no citizen. Form your own conclusions! Well! after all, he heard no treason. Let him play eavesdropper if he finds it consistent with his character as a gentleman.

The captain who brought the extra from Mobile wished to have it reprinted, but it was instantly seized by a Federal officer, who carried it to Butler, who monopolized it; so that will never be heard of again; we must wait for other means of information. The young boy who told us, reminds me very much of Jimmy; he is by no means so handsome, but yet there is something that recalls him; and his voice, though more childish, sounds like Jimmy’s, too. I had an opportunity of writing to Lydia by him, of which I gladly availed myself, and have just finished a really tremendous epistle.

Monday, 7th—No news of importance. We have to haul our water for the camp. The springs where we get our drinking water have become very low on account of the dry weather. Our quartermaster has to send the teams three miles distant for water. I went out about four miles to the south with a squad of men to slaughter some cattle and to bring in some fodder for the mules.

Camp Jones, Flat Top, July 7, 1862. Monday. — The warmest day of the season. The men are building great bowers over their company streets, giving them roomy and airy shelters. At evening they dance under them, and in the daytime they drill in the bayonet exercise and manual of arms. All wish to remain in this camp until some movement is begun which will show us the enemy, or the way out of this country. We shall try to get water by digging wells.

The news of today looks favorable. McClellan seems to have suffered no defeat. He has changed front; been forced (perhaps) to the rear, sustained heavy losses; but his army is in good condition, and has probably inflicted as much injury on the enemy as it has suffered. This is so much better than I anticipated that I feel relieved and satisfied. The taking of Richmond is postponed, but I think it will happen in time to forestall foreign intervention.

There is little or no large game here. We see a great many striped squirrels (chipmunks), doves, quails, a few pigeons and pheasants, and a great many rattlesnakes. I sent Birch the rattles of a seventeen-year-old yesterday. They count three years for the button and a year for each rattle.

There is a pretentious headboard in the graveyard between here and headquarters with the inscription “Anna Eliza Brammer, borned –––“

July 7th. On the march at 4 A. M. We boys did not know we were to march, so awakened merely in time to hurry off without breakfast. Marched 8 miles and encamped on the prairie near the woods. Archie and I took our horses to a corn field. Read a chapter in Bushnell’s “Respectable Sin,” very applicable to myself. Veal noodle soup for supper. Hot day, no covering at night.

Camp near Harrison’s Bar, James River,

Monday, July 7, 1862.

Dear Sister L.:—

I have missed your letters very much, especially for the last two weeks, and I have thought that you might write oftener. I am very lonely now. My two most intimate friends, Henry and Denison, were both wounded on the bloody field of Gaines’ Mill on the 27th of June, and left on the field to the tender mercies of the rebels. Henry, I fear, I never shall see again. He was badly wounded, and everyone in the company except myself thinks he is dead, and I am hoping against hope. Denny was shot through the left hand, and I left them under a tree together. If I should tell you of the narrow escapes I had, you, who know so little of the dangers of the battle, would hardly be able to believe me. Three guns, one after another, were shot to pieces in my hands, and one of these was struck twice before I threw it away. My canteen was shot through, and I was struck in three places by balls, one over the left eye, one in the left shoulder, and one in the left leg, and the deepest wound was not over half an inch, and I came off the field unhurt. God only knows how or why I escaped, but so it was, and though I lost my knapsack containing my little all, I lived “to fight another day.” Saturday night I slept in a corn field in a rain storm with no shelter but the clouds and no bed but the furrow. Sunday night what little sleep I got was on a log in the White Oak Swamp. Monday afternoon I was with the regiment supporting a battery on a hill near the James river, and exposed to a heavy fire of shot and shell. Tuesday forenoon we lay in the woods till the rebels made it so hot it was safer in the open field, and towards night we again went to the front and had another terrible fight. A tent over my shoulder stopped a ball that was speeding straight for my heart, and thus again my life was saved. But I am now alone and the next fight may lay me low with my comrades.

The report sent in from our regiment yesterday gives the names of four hundred and fifty-two killed, wounded and missing in our regiment. Think of that for one regiment! Four hundred and fifty-two out of less than six hundred that went into the fight on Friday. Colonel McLane was shot at almost the first fire, and died without a struggle or a word. Major Naghel followed him an instant after, and our two senior captains were shot during the action. The third one who then took command was wounded, and can only get round now by the help of a horse. I have nothing to say of how the regiment fought. It is not my place, but I am not ashamed yet of the Eighty-third.

What the result of all this fighting will be, I cannot say. The rebels undoubtedly will claim a great victory, as they always do, generally with far less foundation than they now have. McClellan has succeeded in withdrawing his army from a position they could not hold to one that they can hold where his flanks are protected by gunboats and his supplies cannot be cut off. What the rebels have gained I cannot see, except the ability to boast that they have driven McClellan’s army. Their loss is certainly much greater than ours and includes their best General “Stonewall” Jackson.[1] They have but little to boast of.

[1] Note.—This is an error. Jackson was killed at Chancellorsville.

Abbie Howland Woolsey to her sister at Harrison’s Landing.

8 Brevoort Place, July 7,1862.

My dear Georgy : Eliza and Joe came safely through yesterday (Sunday) morning. Jane and I were just going to the front door on our way to church when their hotel coach drove up. They had a pleasant voyage, only Joe says (in joke) he was neglected—Eliza and Miss Lowell directing their attention to other men! . . . Joe hobbled up on his broom-stick for a crutch, and we swarmed round, having so many questions to ask that we didn’t know where to begin, and so were silent. Some broth and sangaree were quickly served and relished. I should say that Charley’s telegram from Washington came Saturday afternoon, and gave us notice enough to send out and get what extra supplies we needed. . . . Mother and Uncle E. drove right in from Astoria, and Joe has had the story to go over a great many times.

From Wikipedia:

The Irish Brigade was an infantry brigade, consisting predominantly of Irish Americans, that served in the Union Army in the American Civil War. The designation of the first regiment in the brigade, the 69th New York Infantry, or the “Fighting 69th”, continued in later wars. The Irish Brigade was known in part for its famous war cry, the “faugh a ballagh”, which is an anglicization of the Irish phrase, fág an bealach, meaning “clear the way”.

From Library of Congress:

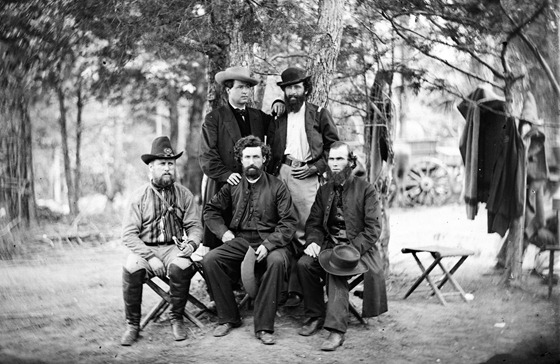

This photo was taken by Alexander Gardner in July 1862 at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia.

Summary: Photo shows: (back row) Patrick Dillon, unidentified; and (front row, left to right) unidentified, James Dillon, and William Corby. The identified men are priests of the Congregation of the Holy Cross, University of Notre Dame. (Source: E. Hogan, Univ. Notre Dame Archives, 2009.)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Record page for this image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000093/PP/

“Wilson Small,” Harrison’s Landing,

Monday, July 7.

Dear Mother, — We reached Washington Saturday morning. Mr. Olmsted transacted his business, and we started on our return Saturday afternoon, bringing with us a cargo of tents for the army. This destroyed our blissful visions of a bath and bed at Willard’s.

Dear Mother, — We reached Washington Saturday morning. Mr. Olmsted transacted his business, and we started on our return Saturday afternoon, bringing with us a cargo of tents for the army. This destroyed our blissful visions of a bath and bed at Willard’s.

I can’t tell you how Washington oppressed me. Its bitter tone towards McClellan fell strangely on our ears, which yet rang with the cheers of the army. We met Commodore Wilkes, who told us he had that moment received his appointment to the naval command on the James River.

On my return here to-day I find your letters, Nos. 16 and 17; also one from the Mayor of Newport, telling me of the munificent gift of the churches, and asking how I should like to have it spent. I have replied, asking him to send half in supplies to us here, and half in money to the treasurer of the Sanitary Commission. How well Newport has done her part in the work! I am often reminded by different branches of the Commission that she was among the very first to send supplies. In Washington I heard it again. Even the particular character of the things she has sent has been praised to me. I wish you would let the community know that my last cases by the “Webster” arrived the night before we left White House. The Medical Director telegraphed Mr. Olmsted to send supplies for the wounded to Savage’s Station. The “Elizabeth” had been seized to tow something; but our other boats had plenty of everything except brandy, so I was delighted to have the cases to send. They went on the last train that got through, together with the cases marked “Miscellaneous.” Please let my generous friends know that coming when they did, their gifts were doubly blessed. Oh! if they could but form an idea of what those things were to those poor wounded, cut off from getting down to our care, and lying parched and agonized and necessarily abandoned by the army. The same day (the day before we left White House) I received a most kind letter from Colonel Vinton, calling my attention to his advertisement for bids, and offering me another contract. I answered gratefully, making proposals for one if I could begin it in September. The letter came, as usual, to Colonel Ingalls’ care; and its official appearance, on business of the Quartermaster’s Department, must have created some curiosity, for it was sent up in hot haste by special messenger.[1]

I had the dearest letter from A. to-day. She says, “Can such things interest you?” Why, nothing interests me so much. I shall come back sick of great events and armies. I want never to see a blue-coat or a gun or an ambulance again. I am glad my letter from Fortress Monroe reached you. To have you say that you get clear ideas from my letters, astonishes me. I write them as one in a dream.

We have come back to find that the army, which we left massed just here, has got into position, and is intrenched or intrenching. General headquarters is moved about a mile and a half inland. General McClellan says positively that he can hold the position. The wounded are all in, and either shipped or cared for on shore. When I say “all,” I mean those within our lines; the most severely wounded we shall never see. Forty of our surgeons are with them, scattered along the line of march; they are prisoners by this time. This is the worst horror of war, and one I cannot trust myself to think of. The Medical Department is doing well by the sick and wounded who have reached this Landing. Four thousand have been already transported on their boats and ours, which come and go with their usual regularity. The gentlemen of the Commission are busily at work issuing stores, and fitting out and sending off the vessels; but it is evident that our work (I mean that of the women at these Commission headquarters) is over. I feel this so much that I begged Mr. Olmsted to let me take the mail-boat as we passed Fortress Monroe last night. But he was unwilling; and in little things as well as in great things no one opposes his will.

We look and hope and pray for reinforcements. Immediate levies should be made, the recruits used in garrisons, and the older troops sent here. The whole question is, Are we in earnest? Is the nation in earnest? or is it the victim of a political game? For God’s sake, for the sake of humanity, let us strike one mighty blow now, and end this rebellion! Surely it cannot be that the nation can’t do this! Then let it be done; and oh! do not sacrifice this noble army. Let every man take arms that can take them, and fill the places of tried men who could come here. At this moment “a strong pull and a pull altogether” would end this rebellion, and send its wretched leaders to their just destruction. This is not my opinion only, it is the sum of all I hear.

The weather is intensely hot. My hand wets and sticks to the paper as I write. The thermometer at the door of my stateroom is 98.° We cannot put our faces out upon deck without blistering them in the fierce glare of sky and water. How I wish Ralph could see the great balloon which is just going up from headquarters!

[1] This, with the allusion on page 1, refers to a contract for the making of flannel army-shirts, given me by Deputy Quartermaster-General D. H. Vinton, U. S. A., for the purpose of giving employment to the families of volunteers and other poor women. During the winter of 1861-62 we made over seventy thousand. The Department paid me fourteen cents a shirt, and furnished the flannel and the buttons. I paid the women eleven cents a shirt (they could easily make four a day, without a machine), and the remaining three cents just covered the cost of linen-thread, transportation to and from New York, office and workroom expenses. The ladies of Newport helped me to cut the shirts.

July 7th. Weather very hot, in consequence of which drills have been suspended. We got a Richmond paper to-day, with a rebel account of the battle of Malvern Hill. It is the Richmond Examiner, of Friday, July 4th. It says “The battle of Tuesday was perhaps the fiercest, and most sanguinary of the series of bloody conflicts, which have signalized each of the last seven days. Early on Tuesday morning, the enemy, from the position to which he had been driven the night before, continued his retreat in a southeasterly direction, towards his gunboats, on James river. At eight o’clock A. M., Magruder recommenced the pursuit, advancing cautiously, but steadily, and shelling the forests and swamps in front, as he progressed. This method of advance was kept up throughout the morning, and until four o’clock P.M. without coming up with the enemy. But between four and five o’clock our troops reached a large open field, a mile long, and three-quarters in width, on the farm of Doctor Carter. The enemy were discovered, (sic) strongly entrenched, in a dense forest on the other side of the field, their artillery, of about fifty pieces, could be plainly seen, bristling on their freshly constructed earthworks. At ten minutes before five o’clock P. M. General Magruder ordered his men to charge across the field, and drive the enemy from their position. Gallantly they spring to the encounter, rushing into the field at a full run. Instantly, from the line of the enemy’s breastworks, a murderous storm of grape and cannister was hurled into their ranks with the most terrible effect. Officers and men went down by the hundreds, but yet undaunted and unwavering, our lines dashed on until two-thirds across the field. Here the carnage from the withering fire of the enemy’s combined batteries and musketry was dreadful. Our line wavered a moment, and fell back into the cover of the woods. Thrice again the effort to carry the position was renewed, but each time with the same results. Night at length rendered further attempt injudicious, and the fight, until ten o’clock, was kept up by the artillery of both sides. To add to the horrors, if not to the dangers of the battle, the enemy’s gunboats from their position at Carl’s Neck, two and a half miles distant, poured on the field, continuous broadsides from their immense rifle guns. Though it is questionable, as we have suggested, whether any serious loss was inflicted on us by the gunboats, the horrors of the fight, were aggravated, by the monster shells, which tore shrieking through the forest, and exploded with a concussion which seemed to shake the solid earth itself. The moral effect on the Yankees of these terror inspiring allies, must have been very great, and in this, we believe, consisted their greatest damage to the army of the South. The battlefield, surveyed through the cold rain of Wednesday morning, presented scenes too shocking to be dwelt on without anguish. The woods and fields mentioned were on the western side, covered with our dead, in all the degrees of violent mutilation, while in the woods on the west of the field lay in about equal numbers, the blue uniformed bodies of the enemy; many of the latter were still alive, having been left by their friends, in their indecent haste to escape from the rebels.

“Great numbers of horses were killed on both sides, and the sight of their distended and mutilated carcases, and the stench proceeding from them, added much to the loathsome horrors of the bloody field. The corn fields, but recently turned by the plowshares, were furrowed and torn by the iron missies. Thousands of round shot and unexploded shells lay upon the surface of the earth; among the latter were many of the enormous shells thrown by the gunboats; they were eight inches in width by twenty-three in length. The ravages of these monsters were everywhere discernible through the forest. In some places long avenues were cut through the tree tops, and here and there, great trees, three and four feet in thickness, were burst open and split to very shreds. In one remarkable respect this battlefield differed in appearance from any of the preceding days. In the track of the enemy’s flight there were no blankets cast away, blue coats, tents, nor clothing, no letters and no wasted commissary stores. He had evidently before reaching this point, (sic) thrown away everything that could retard his hasty retreat. Nothing was to be found on this portion of the field but killed and wounded Yankees, and their guns, and knapsacks.” In another place it says: “The battle of Tuesday evening has been made memorable by its melancholy monuments of carnage, which occurred in that portion of General Magruder’s corps, which had been ordered in very inadequate force, to charge one of the strongest of the enemy’s batteries. There are various explanations of this affair. The fire upon the few regiments who were ordered to take the enemy’s battery, which was supported by two heavy brigades, and which swept the thin line of our devoted men, who had to approach across a stretch of open ground, is said to have been an appalling sight.”

So frank an admission of great loss has never been made before to my knowledge, on the part of the enemy, and it must have been great, indeed, to have them admit so much. The rule seems to be to grossly exaggerate the losses of the Yankees, and minimize their own. That we should have left our wounded on the field at Malvern Hill, is an indelible disgrace, as the enemy were so soundly thrashed they had not energy enough to find out we were gone, until long afterwards the next day. So far as I can find out, we left very few if any wounded, but if one is not an eyewitness, it is difficult to ascertain the truth, even amongst one’s own friends.

The camp is already invaded by a new enemy in overwhelming numbers, and we are completely helpless to protect ourselves; the common house fly is the pest. Where so many of them come from, in so short a time, is a complete mystery; but they are ubiquitous, and the greatest nuisance imaginable. General Richardson, now a major-general, has gone to Fortress Monroe to recoup his health, French is in command of the division, and Colonel J. R. Brooke of the brigade, Zook having gone home to recuperate. Supplies are up in abundance now, and all necessary articles will be replaced immediately. Drilling regularly again.