JULY 17TH.—The people are too jubilant, I fear, over our recent successes near the city. A great many skulkers from the army are seen daily in the streets, and it is said there are 3000 men here subject to conscript duty, who have not been enrolled. The business of purchasing substitutes is prevailing alarmingly.

JULY 17TH.—The people are too jubilant, I fear, over our recent successes near the city. A great many skulkers from the army are seen daily in the streets, and it is said there are 3000 men here subject to conscript duty, who have not been enrolled. The business of purchasing substitutes is prevailing alarmingly.

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

Thursday, 17th—It rained all last night and everybody is thankful, as it has become so dry and dusty. There are a few cases of sickness in our regiment, due to the extremely hot weather—a few cases of typhoid fever and some are suffering from chronic diarrhea.

Camp Green Meadows, Mercer County, Virginia,

July 17, 1862.

Dear Uncle : — . . . I am not satisfied that so good men as two-thirds of this army should be kept idle. New troops could hold the strong defensive positions which are the keys of the Kanawha Valley, while General Cox’s eight or ten good regiments could be sent where work is to be done.

Barring this idea of duty, no position could be pleasanter than the present. I have the Twenty-third Regiment, half a battery, and a company of cavalry under my command stationed on the edge of Dixie — part of us here, fourteen miles, and part at Packs Ferry, nineteen miles from Flat Top, and Colonel Scammon’s and General Cox’s headquarters. This is pleasant. Then, we have a lovely camp, copious cold-water springs, and the lower camp is on the banks of New River, a finer river than the Connecticut at Northampton, with plenty of canoes, flat-boats, and good fishing and swimming. The other side of the river is enemy’s country. We cross foraging parties daily to their side. They do not cross to ours, but are constantly threatening it. We moved here last Sunday, the 13th. On the map you will see our positions in the northeast corner of Mercer County on New River, near the mouth of and north of Bluestone River. Our camps five miles apart — Major Comly commands at the river, I making my headquarters here on the hill. We have pickets and patrols connecting us. I took the six companies to the river, with music, etc., etc., to fish and swim Tuesday.

It is now a year since we entered Virginia. What a difference it makes! Our camp is now a pleasanter place with its bowers and contrivances for comfort than even Spiegel Grove. And it takes no ordering or scolding to get things done. A year ago if a little such work was called for, you would hear grumblers say: “I didn’t come to dig and chop, I could do that at home. I came to fight,” etc., etc. Now springs are opened, bathing places built, bowers, etc., etc., got up as naturally as corn grows. No sickness either — about eight hundred and fifteen to eight hundred and twenty men — none seriously sick and only eight or ten excused from duty. All this is very jolly.

We have been lucky with our little raids in getting horses, cattle, and prisoners. Nothing important enough to blow about, although a more literary regiment would fill the newspapers out of less material. We have lost but one man killed and one taken prisoner during this month. There has been some splendid running by small parties occasionally. Nothing but the enemy’s fear of being ambushed saved four of our officers last Saturday. So far as our adversaries over the river goes, they treat our men taken prisoners very well. The Forty-fifth, Twenty-second, Thirty-sixth, and Fifty-first Virginia are the enemy’s regiments opposed to us. They know us and we know them perfectly well. Prisoners say their scouts hear our roll-calls and that all of them enjoy our music.

There are many discouraging things in the present aspect of affairs, and until frost in October, I expect to hear of disasters in the Southwest. It is impossible to maintain our conquests in that quarter while the low stage of water and the sickness compel us to act on the defensive, but if there is no powerful intervention by foreign powers, we shall be in a condition next December to push them to the Gulf and the Atlantic before winter closes. Any earlier termination, I do not look for.

Two years is an important part of a man’s life in these fast days, but I shall be content if I am mustered out of service at the end of two years from enlistment. — Regards to all.

Sincerely,

R. B. Hayes.

S. BIRCHARD.

17th. Played a little chess. Wrote to Aunt Luna. Slept on the prairie. All the horses of the regiment were out.

Written from the Sea islands of South Carolina.

St. Helena Island, July 17, 1862.

I do want to let you know the little particulars you speak of very much, but there are always so many great things to tell of here that I have no time. Just now we are going through “history” in the removal from Edisto of all the negroes there, consequent upon the evacuation of the island by our troops. The story is this — General McClellan wanting more soldiers, General Stevens and his regiment went North, and we had not enough soldiers left to guard Edisto, which lies near Charleston. So General Hunter ordered the evacuation of the island, first removing all the negroes who wished our protection, and that was all who were there. They embarked in one or two vessels, sixteen hundred in all, with their household effects, pigs, chickens, and babies “promiscuous.” Last night Captain Hooper went to see that they were comfortably established on this island. They have the fashionable watering-place given up to them, with all their old masters’ houses at their disposal. The superintendents laugh about it. They say the negroes go to St. Helenaville for their healths, and the white folks stay on the plantations. I suppose some of the places will be unhealthy, but ours is fortunately situated, as we have a cool wind from the sea every day. These negroes will be rationed and cared for. They say they will get in the cotton here that had to be abandoned when the black regiment was formed. They are quiet and good, anxious to do all they can for the people who are protecting them. They have not the least desire, apparently, to welcome back their old masters, nor to cling to the soil. They want only what Yankees can give them.

We are going to have another change in this household. Mr. Soule,[1] Mrs. Philbrick’s uncle, is coming to preside. He is just made General Superintendent of these two islands, and this will be his headquarters.

Mr. Pierce’s short visit on his return was very pleasant. He came at midnight, in his usual energetic fashion, and stayed some days. General Saxton, his successor, seems a very fine fellow, and most truly anti-slavery. He is quite interested in Nelly Winsor’s movements and plans, she having taken Eustis’ plantation to oversee, as well as this one. She is paid for this by Government fifty dollars per month. Her salary as teacher from the commission will probably soon cease. Ellen has a fine afternoon school and is doing remarkably well with it. She has two Sunday-School classes, one at church, one here. I help in the Sunday-School here and have a class of thirty-six or so at the church.

I will go over one day — an average day — to let you know how I spend my time. If Captain Hooper has to go to Beaufort by the early ferry, we have to get up by six; but if he does not, we lie till after eight, and we about equally divide the days between early and late rising. After breakfast, I feed my three mocking-birds, — how thankful I should be for a decent cage for them! — and then go to the Boston store or the cotton-house and pack boxes to go off to plantations, or clear up the store, or sell — the latter chiefly on Saturdays, when there is a crowd around the door laughing, joking, scolding, crowding. Ellen always goes to the stores when I do, and will stay, as she says she was commissioned expressly to take care of me and work with me. She makes this an excuse or a reason for insisting upon sharing every bit of work I do. About eleven or twelve I come in, wash, sleep, and lunch whenever my nap is out. In the afternoons I expect to write while Ellen has her school, for I do not help her in it, but so many folks come for clothing, or on business, or to be doctored, that I rarely have an hour. Then comes supper and dinner together at any time between six and ten that Captain Hooper gets here. About sundown, I, with Ellen, walk down the little negro street, or “the hill,” as they call it, — though it is as flat as a pond, — to attend my patients. I am sorry to say that Aunt Bess, whose ulcer I had nearly cured, has another on the same leg, and so my skill seems of less avail than I could hope. We had the prettiest little baby born here the other day that I ever saw, and good as gold. It is a great pet with us all. Indeed, it is almost laughable to see what pets all the people are and how they enjoy it. At church, at home, and in the field their own convenience is the first cared for, and compared to them the poor superintendents are “nowhar.” It is too funny to hear them ordering me around in the store — with real good-natured liking for mischief in it, too.

After dinner we sit awhile and talk in the parlor, but the mosquitoes give us no peace. To-night Ellen and I have taken our writing-desks and candle under our mosquito net. I am glad to have good fare. We have nice melons and figs, pretty good corn, tomatoes now and then, bread rarely; hominy, cornbread, and rice waffles being our principal breadstuffs. We have fish every day nearly, but fresh meat never — now and then turtle soup, though. Living on the “fat of the lamb ” is nothing to ours on the fat of the turtle. Our household servants are four in number, besides my Rina, who washes for me and does my chamber-work, besides waiting at table. She is the best old thing in the world and I hope I can take her North with me. … It is grand to run to my private store for nails and tacks, etc., and the sewing-things are invaluable. The pulverized sugar lasts well. Captain Hooper had a letter from Mr. P., in which he speaks of the pleasant times he had here. He will never have so pleasant again, I believe, because he was doing a good work for no pay, and that is a satisfaction not often to be had. The cotton crop here will be a success, I think, and the corn will be plentiful, unless we have some great storms. I wish you could see the wild flowers, the hedges of Adam’s-needle, with heads of white bells a foot or two through and four feet high; the purple pease with blossoms that look like dogtooth violets — just the size — climbing up the cotton-plant with its yellow flower, and making whole fields purple and gold; the passion flowers in the grass; the swinging palmetto sprays.

I send the music. It is not right, but will give you some idea. “Roll, Jordan, Roll” is the finest song.

Fort Barnard, Va., July 17, 1862.

Dear Mother, Sister and Brothers:

It is quite a long time since I last wrote. Have had a spell of sickness. I had a fever, then the shakes, which are very comfortable(!) to have on one. I had to take Quinine for the first time and the taste of it was in my mouth two days after; it loosened every tooth in my head. War news not very exciting. A string of over two hundred teams passed up by here day before yesterday; they are going to help move Pope’s army, but it will take some time to find it.

It has been hot; sweat runs off in streams. George Frye is well. Here I will close and give the Capt. room to write.

Yours,

L. B., Jr.

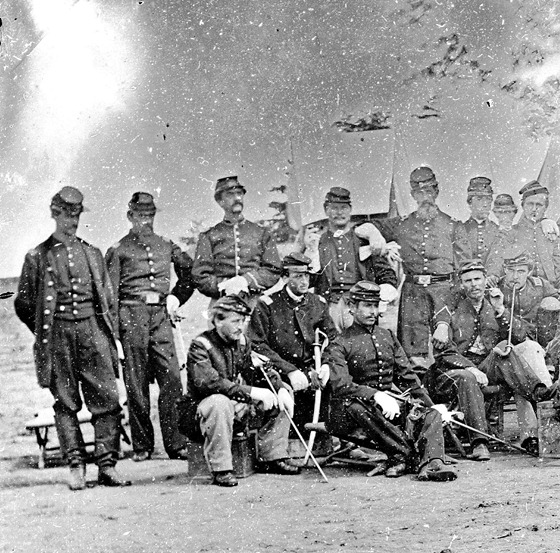

Title: Group of officers. 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery

July 1862; photo by Timothy H O’Sullivan. (cropped from badly aged image and digitally enhanced.)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Record page for image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003005955/PP/

July 17th, Thursday.

July 17th, Thursday.

It is decided that I am to go to New Orleans next week. I hardly know which I dislike most, going or staying. I know I shall be dreadfully homesick; but —

Remember — and keep quiet, Sarah, I beg of you. Everything points to an early attack here. Some say this week. The Federals are cutting down all our beautiful woods near the Penitentiary, to throw up breastworks, some say. Cannon are to be planted on the foundation of Mr. Pike’s new house; everybody is in a state of expectation. Honestly, if Baton Rouge has to be shelled, I shall hate to miss the fun. It will be worth seeing, and I would like to be present, even at the risk of losing my big toe by a shell. But then, by going, I can save many of my clothes, and then Miriam and I can divide when everything is burned — that is one advantage, besides being beneficial by the change of air. They say the town is to be attacked to-night. I don’t believe a word of it.

Oh, I was so distressed this evening! They tell me Mr. Biddle was killed at Vicksburg. I hope it is not true. Suppose it was a shot from Will’s battery?

Thursday, July 17, 1862. (On a raft in Steele’s Bayou.)—Yesterday we went on nicely awhile and at afternoon came to a strange region of rafts, extending about three miles, on which persons were living. Many saluted us, saying they had run away from Vicksburg at the first attempt of the fleet to shell it. On one of these rafts, about twelve feet square, (more likely 12 yards – G.W.C) bagging had been hung up to form three sides of a tent. A bed was in one corner, and on a low chair, with her provisions in jars and boxes grouped round her, sat an old woman feeding a lot of chickens. They were strutting about oblivious to the inconveniences of war, and she looked serenely at ease.

Having moonlight, we had intended to travel till late. But about ten o’clock, the boat beginning to go with great speed, H., who was steering; called to Max:

“Don’t row so fast; we may run against something.”

“I’m hardly pulling at all.”

“Then we’re in what she called the rapids!”

The stream seemed indeed to slope downward, and in a minute a dark line was visible ahead. Max tried to turn, but could not, and in a second more we dashed against this immense raft, only saved from breaking up by the men’s quickness. We got out upon it and ate supper. Then, as the boat was leaking and the current swinging it against the raft, H. and Max thought it safer to watch all night, but told us to go to sleep. It was a strange spot to sleep in—a raft in the middle of a boiling stream, with a wilderness stretching on either side. The moon made ghostly shadows and showed H., sitting still as a ghost, in the stern of the boat, while mingled with the gurgle of the water round the raft beneath was the boom of cannon in the air, solemnly breaking the silence of night. It drizzled now and then, and the mosquitoes swarmed over us. My fan and umbrella had been knocked overboard, so I had no weapon against them. Fatigue, however, overcomes everything, and I contrived to sleep.

H. roused us at dawn. Reeney found light-wood enough on the raft to make a good fire for coffee, which never tasted better. Then all hands assisted in unloading; a rope was fastened to the boat, Max got in, H. held the rope on the raft, and, by much pulling and pushing, it was forced through a narrow passage to the farther side. Here it had to be calked, and while that was being done we improvised a dressing-room in the shadow of our big trunks. (During the trip I had to keep the time, therefore properly to secure belt and watch was always an anxious part of my toilet.) The boat is now repacked, and while Annie and Reeney are washing cups I have scribbled, wishing much that mine were the hand of an artist.

![]()

______

Note: To protect Mrs. Miller’s job as a teacher in New Orleans, the diary was published anonymously, edited by G. W. Cable, names were changed and initials were often used instead of full names — and even the initials differed from the real person’s initials.July 17.—A detachment of the Union army, under Gen. Pope, this day entered the town of Gordonsville, Va., unopposed, and destroyed the railroad at that place, being the junction of the Orange and Alexandria and Virginia Central Railroads, together with a great quantity of rebel army supplies gathered at that point

—Cynthiana, Ky., was captured by a party of rebel troops, under Col. John H. Morgan, after a severe engagement with the National forces occupying the town, under the command of Lieut. Col. Landrum.—(Doc. 89.)

—The British schooner William, captured off the coast of Texas by the National steamer De Soto, arrived at Key West, Fla.—Major-General Halleck, having relinquished the command of the department of the Mississippi, left Corinth for Washington, D. C, accompanied by General Cullum, Col. Kelton, and an aid-de-camp.—The bill authorizing the issue of postage and other government stamps as currency, and prohibiting banks and other corporations or individuals from issuing notes below the denomination of one dollar for circulation, was passed by the House of Representatives and signed by the President.

—President Lincoln sent a special message to Congress, informing it that as he had considered the bill for an act to suppress insurrection, to punish treason and rebellion, to seize and confiscate the property of rebels, and the joint resolution explanatory of the act, as being substantially one, he had approved and signed both. Before the President was informed of the passage of the resolution, he had prepared the draft of a message stating objections to the bill becoming a law, a copy of which draft he transmitted to Congress with the special message.

—The Congress of the United States adjourned sine die.—At Louisville, Ky., both branches of the Common Council of that city adopted an ordinance compelling the Board of School Trustees to require all professors and teachers of the public schools, before entering on their duties, to appear before the Mayor and take oath to support the Constitutions of the United States and Kentucky, and to be true and loyal citizens thereof.—Gen. Nelson arrived at Nashville, Tenn., with large reenforcements, and assumed command there.

—A scouting-party of ten men, under Lieut. Roberts, of the First Kentucky (Wolford’s) cavalry, when about fifteen miles from Columbia, Tenn., were attacked by a body of sixty rebels. The Union party retired to a house in the neighborhood, from which they fought the rebels six hours, when they finally retreated. Several of the rebels fell. The Union party lost none.

—Enthusiastic meetings were this day held at Bangor, Me., Bridgeport, Ct, and Auburn, N. Y., for the purpose of promoting enlistments into the army, under the call of the President for more troops.