JULY 9TH.—Lee has turned the tide, and I shall not be surprised if we have a long career of successes. Bragg, and Kirby Smith, and Loring are in motion at last, and Tennessee and Kentucky, and perhaps Missouri, will rise again in “Rebellion.”

Monday, July 9, 2012

Wednesday, 9th July.

Poor Miriam! Poor Sarah! they are disgraced again! Last night we were all sitting on the balcony in the moonlight, singing as usual with our guitar. I have been so accustomed to hear father say in the evening, “Come, girls! where is my concert?” and he took so much pleasure in listening, that I could not think singing in the balcony was so very dreadful, since he encouraged us in it. But last night changed all my ideas. We noticed Federals, both officers and soldiers, pass singly, or by twos or threes at different times, but as we were not singing for their benefit, and they were evidently attending to their own affairs, there was no necessity of noticing them at all.

But about half-past nine, after we had sung two or three dozen others, we commenced “Mary of Argyle.” As the last word died away, while the chords were still vibrating, came a sound of — clapping hands, in short! Down went every string of the guitar; Charlie cried, “I told you so!” and ordered an immediate retreat; Miriam objected, as undignified, but renounced the guitar; mother sprang to her feet, and closed the front windows in an instant, whereupon, dignified or not, we all evacuated the gallery and fell back into the house. All this was done in a few minutes, and as quietly as possible; and while the gas was being turned off downstairs, Miriam and I flew upstairs, — I confess I was mortified to death, very, very much ashamed, — but we wanted to see the guilty party, for from below they were invisible. We stole out on the front balcony above, and in front of the house that used to be Gibbes’s, we beheld one of the culprits. At the sight of the creature, my mortification vanished in intense compassion for his. He was standing under the tree, half in the moonlight, his hands in his pockets, looking at the extinction of light below, with the true state of affairs dawning on his astonished mind, and looking by no means satisfied with himself! Such an abashed creature! He looked just as though he had received a kick, that, conscious of deserving, he dared not return! While he yet gazed on the house in silent amazement and consternation, hands still forlornly searching his pockets, as though for a reason for our behavior, from under the dark shadow of the tree another slowly picked himself up from the ground — hope he was not knocked down by surprise —and joined the first. His hands sought his pockets, too, and, if possible, he looked more mortified than the other. After looking for some time at the house, satisfied that they had put an end to future singing from the gallery, they walked slowly away, turning back every now and then to be certain that it was a fact. If ever I saw two mortified, hangdog-looking men, they were these two as they took their way home. Was it not shocking?

But they could not have meant it merely to be insulting or they would have placed themselves in full view of us, rather than out of sight, under the trees. Perhaps they were thinking of their own homes, instead of us.

Wednesday, 9th—Nothing of importance today. Our regiment went out on picket again. Our picket line and reserve post are both in heavy timber and so we do not have to be in the hot sun while on duty.

To Mrs. Lyon.

July 9, 1862.—I see there has been terrible fighting at Richmond, we fighting, as usual, against fearful odds. My only surprise is that our army was not annihilated. This check, unless speedily retrieved, will prolong the war a year, but the effect of it, I think, will be to send immense reinforcements to the field and insure a more vigorous and more severe prosecution of the war. The time has come, or will soon come, to march through this nest of vipers with fire and sword, to liberate every slave. I would like to help do that. Wisconsin has sent over twenty thousand men to the field, and must send within ninety days five thousand more, even though the drafting process be resorted to. I do not know as it is right, but life seems of no value to me unless we can crush out this rebellion and restore our Government; and we shall do it, if every man is driven to the field and our rivers run red with blood for a generation.

9th. Marched all the forenoon, and went only five miles forward. So many blunders. Encamped on Grand River near it on the edge of the woods, good place.

Harrison’s Landing, James River, Va.,

Wednesday, July 9, 1862.

Dear Father:—

Having leisure to-day and knowing that you are glad to hear from me often in these troublous times. I will write a little, though there is nothing of much interest to write.

As for myself, I have great reason to be thankful that it is as well with me as it is. The final report of our loss gives the names of four hundred and fifty-two killed, wounded and missing in our regiment. This seems like a fearful loss, as we went into the fight on the 27th with less than six hundred men. Of the small number who remain, not half are strong enough to stand a march of ten miles. A great many are sick, not very sick, but worn out, weak, and unable to endure full duty. Last night the President was here, and our brigade was out in full strength for a review. Every man who could carry his gun one hundred rods was out, and while we were waiting we stacked arms, and our regiment had thirty-two stacks, or one hundred and twenty-eight men out. If ordered out for a march not more than one hundred of these could go. This will give you an idea of how we are reduced. I am as well off, I think, as any one in the regiment. I am not as strong as I might be, but I charge it to the weakening effect of the hot weather as much as anything. I am entirely free from that bane of the soldier, diarrhea, etc., from which so many suffer. Hundreds of our soldiers have not seen a day in six months when they were what I should consider well. My weight is only 117 pounds, but what there is of me is bone and muscle. I attribute my good health in part to my constant use of woolen drawers and shirts. I never have gone without them a day since I have been in the service. I have now but one pair of drawers; one pair and one of the shirts you got for me when I first enlisted were left in my knapsack. They wore like iron. Another cause of sickness among our men is spending too much on the sutler. His wares are generally of a kind that do more harm than good. I have spent but very little with him for eatables, and though our diet is a constant succession of the same articles, and these not very tempting, I believe it is the best plan to live on our rations alone. The climate and exposure, with the bad water, are enough to contend against. Sometimes we have excellent water, and again we can get nothing but roily swamp water. I have drunk a good deal of water that at home would have turned my stomach, but in such circumstances I drink as little as possible, and make it into coffee. We usually have plenty of coffee and sugar when we can get our rations.

I am very anxious to know how the call for more troops will be responded to. It seems to me all important that the people should rise immediately. A week’s hesitancy may bring results terrible to contemplate. It seems to me that nothing but such a show of our power and purpose to put a speedy end to the rebellion as will awe the European powers and force them to respect us can save us from foreign intervention and a war that no one can see the end of. There is no use in grumbling at this secretary and that general while we let things take the course they are now taking. McClellan should have been reinforced when he called for more troops. If he had been listened to and supported, Richmond would have been ours before this, and the backbone of the rebellion broken. There is a fearful responsibility on the shoulders of the men who have denied his requests and forced him to his present position. I don’t pretend to know who is to blame about the matter, but someone is. No one in the army thinks of blaming McClellan. His men have the fullest confidence in his ability to do all that any living man can do with the force at his disposal, but anyone who saw how the rebels fought at Malvern Hill on Tuesday, and saw them pour five different lines of fresh troops against our one, can tell why he does not take Richmond. We are not whipped and cannot be, but we are obliged to take the defensive instead of the offensive in our fighting. The rebels are before us in such overwhelming numbers that I cannot see how it is possible for us to take Richmond without a great increase of our present force. We must have it or give up all.

I understand that an effort is being made to have us sent to Erie to recruit. I see but one objection and that is this—there are a great many regiments as badly or nearly as badly cut up as ours. To send them away will weaken our force here, already far too small. But we are not in condition to be effective at present and I am not sure but it would be best under the circumstances. Men who enlist would much rather enlist in a regiment that has been tried and earned a name than in a new regiment, and, if we were in Erie, had a camp and were drilling so that men could see the regiment and knew what they were going into, we would get ten men where we could one by staying here and sending out recruiting officers. I don’t know, I am sure, what is best, but I hope something will be done soon.

I have not heard anything from E. in a long time. I expect that when the call is made and recruiting commences in your vicinity, he will want to enlist, but don’t let him. I am convinced he never would stand it. His looks may be stouter than mine, but he has not the endurance, and if he should enlist he would be sorry for it afterwards. One representative from the family will do. It is more than probable that I shall not outlive the war, and you will want him left. Now that sounds selfish, I know, but I cannot help it. I don’t want him in the army. If I could just have taken him for one hour from home and put him on the field at Gaines’ Mill on Friday, it would have banished all thoughts of enlisting from his mind instanter. Let him see a ditch half full of dead and wounded men piled on each other; let him see men fall all round him and hear them beg for water; let him see one-quarter of the awful sights of the battlefield, and he would be content to keep away. This may be a weak spot in me, but I cannot help it. I feel as though I could not have him enlist. I presume he thinks he has a hard time where he is, but if he only knew the truth he would never want to leave.

It is past time for me to get dinner, and still I am writing. I only thought of writing a short letter, but this would hardly be called very short.

We are getting some new things in place of those we lost—new blankets, pants, shirts, socks, blouses, haversacks, etc., are furnished as fast as possible.

I hope we shall get our pay soon. Two months pay is due and I have not a dollar left. A dollar here is not more than twenty-five cents at home. Write to me as soon as you can.

P. S.—Wicks is well. Not a word from Henry or Denny yet.

Wednesday, 9th.—Moved over to Cherokee Springs; remained until the 29th, enjoying myself as best I could. Had several big games of Ten Pins.

(Note: picture is of an unidentified Confederate soldier.)

Georgeanna Muirson Woolsey to Frederick Law Olmsted.

Georgeanna Muirson Woolsey to Frederick Law Olmsted.

Washington.

My dear Mr. Olmsted: Can the Sanitary Commission do anything to prevent a repetition of the inhuman treatment the sick received last week, on their way from Jamestown to Alexandria? 150 men were packed in one canal boat between decks, stowed so closely together that they were literally unable to turn over; without mattresses, without food, without decent attention from the time they left till their arrival. Among them were three or four men with the worst kind of measles put in with all the rest: one of them died on the boat, and another on the way from the boat to the hospital, and it will be wonderful if the disease has not communicated itself to others among the 150. There was of course no ventilation, and the men say that they suffered greatly from bad air. A medical officer came down with the boat and is perhaps not responsible for the state of things on board; some one must be, however, and it may save further suffering if the affair could be made public. We heard this story through a friend who was in Alexandria when the boat arrived and has known all the facts of the case.

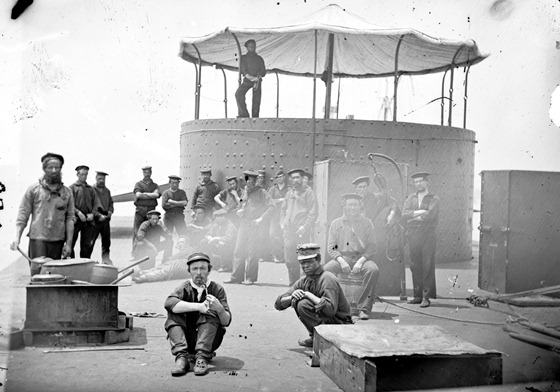

James River, Va. Sailors on deck of U.S.S. Monitor; cookstove at left; July 9, 1862

From Wikipedia:

From Library of Congress:

Photographed by James F. Gibson.

Photographs of the Federal Navy, and seaborne expeditions against the Atlantic Coast of the Confederacy

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Record page for image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000716/PP/

July 9.—The National transport steamer Canonicus was fired into by the rebels, a few miles below Harrison’s Landing, on the James River, Va. —In the New-Hampshire Legislature resolutions were unanimously passed, pledging the State to furnish her full quota of soldiers under the call of President Lincoln.

—Public meetings were held in England, praying the government to use its influence to bring about a reconciliation between the Northern and Southern States of America, as it was from America alone that an immediate supply of cotton could be expected; and if need there should be, that the British government should not hesitate to acknowledge the independence of the Southern States.

—A fight occurred near Tompkinsville, Ky., between a body of one thousand five hundred guerrillas, under Morgan, and the Third battalion of Pennsylvania cavalry, numbering about two hundred and fifty men, under the command of Major Jordan, in which the Nationals were routed, with a loss of four killed, six wounded, and nineteen taken prisoners.

—Hamilton, N. C, was occupied by the National forces under the command of Capt. Hammel, of Hawkins’s N. Y. Zouaves.—(Doc. 148.)