JULY 3D. —Our wounded are now coming in fast, under the direction of the Ambulance Committee. I give passports to no one not having legitimate business on the field to pass the pickets of the army. There is no pilfering on this field of battle; no “Plug Ugly” detectives stripping dead colonels, and, Falstaff like, claiming to be made “either Earl or Duke” for killing them.

So great is the demand for vehicles that the brother of a North Carolina major, reported mortally wounded, paid $100 for a hack to bring his brother into the city. He returned with him a few hours after, and, fortunately, found him to be not even dangerously wounded.

I suffer no physicians not belonging to the army to go upon the battle-field without taking amputating instruments with them, and no private vehicle without binding the drivers to bring in two or more of the wounded.

There are fifty hospitals in the city, fast filling with the sick and wounded. I have seen men in my office and walking in the streets, whose arms have been amputated within the last three days. The realization of a great victory seems to give them strength.

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

Thursday night, July 3d.

Another day of sickening suspense. This evening, about three, came the rumor that there was to be an attack on the town to-night, or early in the morning, and we had best be prepared for anything. I can’t say I believe it, but in spite of my distrust, I made my preparations. First of all I made a charming improvement in my knapsack, alias pillow-case, by sewing a strong black band down each side of the centre from the bottom to the top, when it is carried back and fastened below again, allowing me to pass my arms through, and thus present the appearance of an old peddler. Miriam’s I secured also, and tied all our laces in a handkerchief ready to lay it in the last thing.

But the interior of my bag! — what a medley it is! First, I believe, I have secured four underskirts, three chemises, as many pairs of stockings, two under-bodies, the prayer book father gave me, “Tennyson” that Harry gave me when I was fourteen, two unmade muslins, a white mull, English grenadine trimmed with lilac, and a purple linen, and nightgown. Then, I must have Lavinia’s daguerreotype, and how could I leave Will’s, when perhaps he was dead? Besides, Howell’s and Will Carter’s were with him, and one single case did not matter. But there was Tom Barker’s I would like to keep, and oh! let’s take Mr. Stone’s! and I can’t slight Mr. Dunnington, for these two have been too kind to Jimmy for me to forget; and poor Captain Huger is dead, and I will keep his, so they all went together. A box of pens, too, was indispensable, and a case of French notepaper, and a bundle of Harry’s letters were added. Miriam insisted on the old diary that preceded this, and found place for it, though I am afraid if she knew what trash she was to carry, she would retract before going farther.

It makes me heartsick to see the utter ruin we will be plunged in if forced to run to-night. Not a hundredth part of what I most value can be saved — if I counted my letters and papers, not a thousandth. But I cannot believe we will run to-night. The soldiers tell whoever questions them that there will be a fight before morning, but I believe it must be to alarm them. Though what looks suspicious is, that the officers said — to whom is not stated — that the ladies must not be uneasy if they heard cannon tonight, as they would probably commence to celebrate the Fourth of July about twelve o’clock. What does it mean? I repeat, I don’t believe a word of it; yet I have not yet met the woman or child who is not prepared to fly. Rose knocked at the door just now to show her preparations. Her only thought seems to be mother’s silver, so she has quietly taken possession of our shoe-bag, which is a long sack for odds and ends with cases for shoes outside, and has filled it with all the contents of the silver-box; this hung over her arm, and carrying Louis and Sarah, this young Samson says she will be ready to fly.

I don’t believe it, yet here I sit, my knapsack serving me for a desk, my seat the chair on which I have carefully spread my clothes in order. At my elbow lies my running- or treasure-bag, surrounded by my combs filled with hair-pins, starch, and a band I was embroidering, etc.; near it lie our combs, etc., and the whole is crowned by my dagger; — by the way, I must add Miriam’s pistol which she has forgotten, though over there lies her knapsack ready, too, with our bonnets and veils.

It is long past eleven, and no sound of the cannon. Bah! I do not expect it. “I’ll lay me down and sleep in peace, for Thou only, Lord, makest me to dwell in safety.” Good-night! I wake up to-morrow the same as usual, and be disappointed that my trouble was unnecessary.

Thursday, 3d—The Eleventh Iowa went out on picket duty. I was on guard at division headquarters, my post being in a large orchard, and my orders were to keep all soldiers out of it.[1]

[1] Such orders soon got to be a joke with the men, they in a quiet way giving the commanding officers to understand that they did not go down South to protect Confederate property. In a short time all guards were taken from orchards or anything which the men wanted for food.—A. O. D.

Camp Jones, July 3, 1862. Wednesday [Thursday], — A fine bright day. General Cox is trying to get our army transferred to General Pope’s command in eastern Virginia.

The dispatches received this beautiful afternoon fill me with sorrow. We have an obscure account of the late battle or battles at Richmond. There is an effort to conceal the extent of the disaster, but the impression left is that McClellan’s grand army has been defeated before Richmond!! If so, and the enemy is active and energetic, they will drive him out of the Peninsula, gather fresh energy everywhere, and push us to the wall in all directions. Foreign nations will intervene and the Southern Confederacy be established.

Now for courage and clear-headed sagacity. Nothing else will save us. Let slavery be destroyed and this sore disaster may yet do good.

3rd. Thursday. In saddles at three A. M. Rode 18 miles. Encamped on Grand River.

“Wilson Small,” Harrison’s Landing,

July 3.

Dear A., — As I write I glance from time to time at the Army of the Potomac, massed on the plain before me, —- an army driven from its position because it could not get reinforcements to render that position tenable; forced every day of its retreat to turn and give battle; an army just one third less than it was: and yet it comes in from seven days’ fighting, marching, fasting, in gallant spirits, and making the proud boast for itself and its commander that it has not only marched with its face backward to the enemy, but has inflicted three times the loss it has borne, and that the little spot of its refuge rings with its cheers.

And yet the sad truth cannot be concealed: our position is very hazardous. What I hear said is such as this: “Unless we have reinforcements, what can we do? Must McClellan fight another bloody battle in a struggle for life, or surrender? Give us reinforcements, and all is well. We have got the right base now. We could not have it at first; we made another; that other the Government made it impossible for us to maintain. Day by day we saw it growing untenable. We now have the true base of operations against Richmond. The sacrifice? Yes! but who compelled it? The nation must see to that. The army and McClellan have done their part, and nobly have they done it. Let them now be strengthened, and all is well, or better than before.” This is the one tone. No wonder that they feel in spirits, they have done their duty; and I look in their poor worn faces and feel that their deepest honor in life will be that they belonged to the beaten Army of the Potomac — and yet, not beaten ; everything that that is, except precisely the thing it is.

I am sitting on deck. Poor Miss Lowell, whose gallant brother was killed yesterday, is beside me. She belongs to the “Daniel Webster,” which is to load up this afternoon. We are lying a stone’s throw from a long wharf, and a little in-shore of it. My eye can follow the lines within which our army lies. The immediate prospect is a sandy shore, with a sandy slope behind it, up and down which the cavalry are ceaselessly passing to water and swim their horses in the river. At the head of the wharf are General Keyes’s- headquarters; to the right are General Franklin’s; and a little farther back, General Porter’s; while the eighth of a mile back upon the left, General Headquarters are said to be. The long wharf is a moving mass of human beings: on one side, a stream of men unloading the commissariat and other stores; on the other, a sad procession of wounded, feebly crawling down from the Harrison House and along the beach and wharf to go on board the transports. The medical authorities are doing well by them. The Harrison House is made into a hospital, and the men are comfortable (so say our gentlemen, who have been among them); the slight cases are lying on the lawn and under the trees. To-day — thank God for the great mercy! —is cloudy, without rain. I know nothing of them personally. We women are not yet permitted to go ashore, and I try to believe, as I am told, that it is impossible we should.

A new Medical Director of the army has been appointed, for which we are deeply thankful. He is now on board the “Small,” and has just stood near me for a few moments, talking to some one, so that I could observe him, —- one looks into faces so much here! His gave me a sad calmness. Such a worn face, — worn in the cause of suffering; full, it seemed to me, of a strong earnestness in his work. How much at this moment is fresbly laid upon him![1] I can’t tell you anything of my own knowledge about the wounded; but I judge from what I am told that there is not much suffering, and no privation among those who are here. They are chiefly slightly wounded and exhausted men. But where are the others? Alas! where? This is war, and there’s no more to be said about it.

But I was telling you what I see from the deck as I sit writing, — of course with countless interruptions and runnings below to give this poor surgeon or that poor chaplain as many comforts for their sick men as they can carry off in their saddle-bags, or tied up in pillow-cases. Now, suppose I tell you that I am seeing and hearing war at this moment in the shape of shells bursting within our lines directly in front of me! And there’s the wonderful little “Monitor” firing her great eleven-inch gun — there it goes, boom! and then the screwing, screaming, rushing sound of the great rifle-shell! Talk of wonders! there never was anything in that line like the “Monitor.” You don’t imagine what a little tray of a thing she is, — I did n’t. Why, the sides of her captain’s gig, which is towing aft, are higher than hers! She lay close by us for an hour this morning, and at first I conld not believe she was the real thing.

[1] Dr. Letterman. Soon after his appointment he reorganized his department, remodelled the medical corps, established a plan for division field-hospitals after a battle, and got an efficient ambulance system into good working order. Thus when the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, etc., occurred, the Medical Department, its surgeons and supplies, were well prepared, and nothing at all like the suffering after Fair Oaks occurred again.

3rd.—This morning the men looked haggard and worn. Some slept; more shivered with cold the night through, and in my morning round to look after the health of the regiment, I found men standing upright, without any support, and fast asleep. There was no wood within half a mile of us to make fires. Not a step could be taken without sinking to the ankles in mud and water; and thus opened the day of the 3d of July. All felt depressed, but there was little or no murmuring. What a wonderful army! And yet it has been a whole year in the field and has accomplished nothing. Who is to blame? We are in a bow of the James River, with the enemy in our front. We can retreat no further, and when, early in the morning, a few vollies of musketry were heard, all felt that the trying time had come, and that the death struggle must be had to-day. We were mistaken. After the few vollies, the firing ceased, and all has been comparatively quiet. The thirst had been quenched, and the flow of blood, at least for the day, is checked. To-morrow will be the Fourth of July, and the calm of the 3d portends that this Fourth is to be a day of travail, and, perhaps, the birth-day of another nation.

Jane Eliza Newton Woolsey to her daughter.

July 3, ’62.

My dear Eliza: What times you are living through! in the very midst, too, of everything as you are !—and how dark, very dark, it all looks to us this morning as we read the last “reliable ” accounts from the army before Richmond! Think of six days’ continuous fighting. When I looked over the list of horrors, my first thought and exclamation was, “just think what Joe has been spared!” I really look upon his “slight wound” as the greatest blessing which could have happened to us all, and I am thankful for it. It may have been the means of saving his life. Abby is writing you, but I put in my own words of tender love and sympathy. . . . I rejoice that Charley is at hand with you.

Thursday, July 3d.—Went out into the Lowry neighborhood to visit kin.

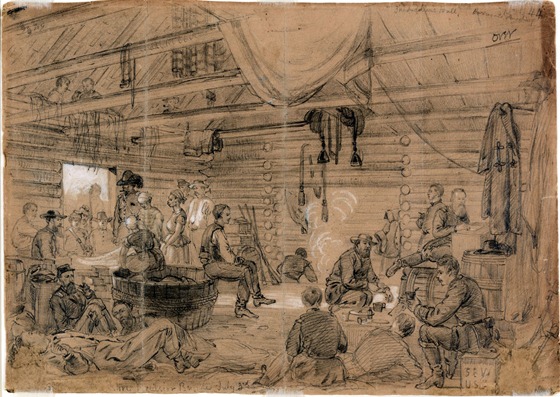

(Note: picture is of an unidentified Confederate soldier.)

From Library of Congress:

- Signed lower right: Waud.

- Title inscribed upper right.

- Inscribed lower left: Sk[etch in Sutlers’s] store Excelsior Brigade July 3rd.

- Note that the figure seated to the left of the doorway bears a close resemblance to Waud and was probably intended as a self-portrait.

- Published in: Harper’s Weekly, August 9, 1862, p. 500.

- Inscribed on box in image: 1000 … Cartridges Call 52.

Part of Morgan collection of Civil War drawings.. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Record page for this image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004661191/