JULY 22D.—Today Gen. Winder came into my office in a passion with a passport in his hand which I had given, a week before, to Mr. Collier, of Petersburg, on the order of the Assistant Secretary of War—threatening me with vengeance and the terrors of Castle Godwin, his Bastile! if I granted any more passports to Petersburg where he was military commander, that city being likewise under martial law. I simply uttered a defiance, and he departed, boiling over with rage.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

July 22d, Tuesday.

Another such day, and there is the end of me! Charlie decided to send Lilly and the children into the country early to-morrow morning, and get them safely out of this doomed town. Mother, Miriam, and I were to remain here alone. Take the children away, and I can stand whatever is to come; but this constant alarm, with five babies in the house, is too much for any of us. So we gladly packed their trunks and got them ready, and then news came pouring in.

First a negro man just from the country told Lilly that our soldiers were swarming out there, that he had never seen so many men. Then Dena wrote us that a Mrs. Bryan had received a letter from her son, praying her not to be in Baton Rouge after Wednesday morning, as they were to attack to-morrow. Then a man came to Charlie, and told him that though he was on parole, yet as a Mason he must beg him not to let his wife sleep in town to-night; to get her away before sunset. But it is impossible for her to start before morning. Hearing so many rumors, all pointing to the same time, we began to believe there might be some danger; so I packed all necessary clothing that could be dispensed with now in a large trunk for mother, Miriam, and me, and got it ready to send out in the country to Mrs. Williams. All told, I have but eight dresses left; so I’ll have to be particular. I am wealthy, compared to what I would have been Sunday night, for then I had but two in my sack, and now I have my best in the trunk. If the attack comes before the trunk gets off, or if the trunk is lost, we will verily be beggars; for I pack well, and it contains everything of any value in clothing.

The excitement is on the increase, I think. Everybody is crazy to leave town.

22nd.—I have received letters from my family to-day. One of them says, “We are not feeling well this morning.” “Who is not, and what is the matter? It is a dreadful thought that we must be thus separated from family without the slightest prospect of being able to see them when we know they are suffering.

Tuesday, 22d—We removed our tents and had a general cleanup of the camp. We made brush brooms, took down all tents, swept the ground, then pitched our tents again.

We lay here two or three days taking in coal, &c., and it was finally arranged that the iron-clad Essex should run down by the batteries, with a prospect of destroying the ram, and of relieving the wooden ships which had already been ordered down the river. Accordingly, on the morning of the 22d we got under way, and awaited the appearance from above, ready to attack the ram or assist the Essex, as the case might require. At six o’clock firing commenced, and soon the Essex appeared, followed by a small wooden ram, and proceeded down through the batteries, giving the rain a broadside as she passed her, while the whole rebel line opened upon her. I here witnessed a most sublime picture in naval operations,—a lone vessel running the gauntlet of some thirty cannon placed in the hillside, raining a shower of shot and shell thickly around her. She escaped, however, with the loss of one man killed, and a single shot through her armor.

22nd. Read in “Guy Mannering.” Issued rations for eleven days. Horses got away. Looked all over the country until the next day at 4 P. M., when we marched.

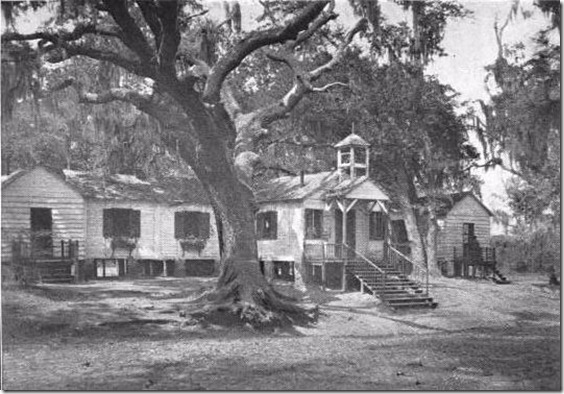

Written from the Sea islands of South Carolina.

The Old Penn School

[Diary] July 22.

Our guns have come! Captain Thorndyke brought over twenty and gave Nelly instructions. Commodore Du Pont was here this afternoon. The people came running to the school-room — “Oh, Miss Ellen, de gunboat come!” I believe they thought we were to be shelled out. Ellen, Nelly, and I went down to the bluff and there lay a steamboat in front of Eina’s house, and a gig was putting off with flag flying and oars in time. Presently a very imposing uniformed party landed, and, coming up the bluff, Commodore Du Pont introduced himself and staff. We invited him in. He said he had come to explore the creek and to see a plantation. They stayed only about ten minutes, were very agreeable and took leave. Commodore Du Pont is a very large and fine-looking man. He invited us all to visit the Wabash and seemed really to wish it.

Somewhere about July 14, ’62, Charley and G. must have gone home from Harrison’s Landing, probably in a returning hospital ship. The record is lacking—Sarah Woolsey’s letter of July 22 being the first mention of it. She had been serving all this time at the New Haven Hospital.

Sarah Chauncey Woolsey to Georgeanna Woolsey.

New Haven.

At The Barrack Hospital, July 22.

When the family leave you a little gap of time, write me one line to make me feel that you are really so near again. I cannot help hoping that if you go back, there may be a vacancy near you which I can fill. The work here is very satisfactory in its way, but is likely to come to an end before long if the decision about “Hospitals within military limits” is carried out. . . .

This is Sunday, and I have been here since half past nine—it being about 5 P. M. now . . . It has not been very Sunday-like, as I’ve mended clothes, and given out sheets, and made a pudding, but somehow it seems proper. Mary would laugh if she knew one thing that I’ve been doing—distributing copies of “A Rainy Day in Camp” to sick soldiers, who liked it vastly. I had it printed in one of our papers for the purpose. To-morrow I am going to change employments—take Miss Young’s place in the kitchen, and let her have a day’s rest, while Mrs. Hunt supplies mine here. Meantime as a beginning I must go and heat some beef tea for a poor fellow who hates to eat, and has to be coaxed into his solids by an after promise of pudding and jelly. . . .

P. S —Have come back from service and administered the beef tea, though it was an awful job. The man gave continual howls, first because the tea was warm, then because I tried to help him hold a tumbler, then because I fanned him too hard, and I thought each time I had hurt him and grew so nervous that I could have cried. Beside, there is a boy in that tent—an awful boy with no arms, who swears so frightfully (all the time he isn’t screeching for currant pie, or fried meat, or some other indigestible), that he turns you blue as you listen.

July 23d. [22d] Returned to camp after a delightful and refreshing little jaunt. The sail down the river was magnificent. There were few passengers, mostly invalided officers, but a very agreeable lot of fellows, of course. The ship carried at her cross trees, boiler iron nests, in which riflemen were stationed, watching the shore all along the route. Her guns were shotted and run out ready for instant work, and all about one tended to a delightful exhilaration. I sat well forward, and was in ecstasy to find myself on the water again. The James is a beautiful river, with fine commanding banks, abrupt in many places, and mostly wooded to the water’s edge. It is considered a dangerous route, and everyone is on the alert for a concealed enemy along the shores. We met scores of transports, gunboats, and troop ships; and there was plenty to occupy one’s attention. Arriving at the fort, I went to dine at the hotel, and sat down to a regular dinner, at a regular table, for the first time in over a year. The situation was embarrassing at first, but I found myself, as an officer from the front, of considerable importance, which was equally unexpected and agreeable. I met many civilians, who were all anxious to talk about the war. I made myself agreeable, and did as little boasting perhaps as the situation allowed.

They told me General Sumner was considered one of the principal heroes of the last campaign. After dinner I looked over the fortress, which is the largest regular work, I think, in the United States. It is surrounded by a moat full of water and has a fine array of mounted guns peeping over the ramparts. When I went to my room at night, the first sight of a regular bed almost took away my breath, and I was strongly tempted to take the floor in preference. I got in after some hesitation and found it comfortable, but very strange. The next day I visited the negroes’ quarters, bought various articles for the colonel and myself; sent the diary home, also a rebel officer’s sword, captured at Savage’s Station, and then went on board a transport, bound back to the camp. The return sail was equally agreeable. I felt like returning home from a strange country; the regiment is now, in fact, my home, where all my interests center.

July 22.—Major-General Sherman assumed command at Memphis, Tenn. Four hundred citizens took the oath of allegiance, and one hundred and thirty were provided with passes to go to the South.—General Dix, on the part of the United States, and Gen. D. H. Hill, for the rebel government, made an arrangement for an immediate and general exchange of prisoners.—(Doc. 103.)

—President Lincoln issued an order in reference to foreign residents in the United States. The ministers of foreign powers having complained to the government that subjects of such powers were forced into taking the oath of allegiance, the President ordered that military commanders abstain from imposing such obligations in future, but in lieu adopt such other restraints as they might deem necessary for the public safety.

—The steamer Ceres was fired into by the rebels at a point on the Mississippi, below Vicksburgh, Miss., killing Capt Brooks, of the Seventh Vermont regiment, besides inflicting other injuries.

—Governor Gamble, of Missouri, in view of the existence of numerous bands of guerrillas in different parts of that State, who were engaged in robbing and murdering peaceable citizens for no other cause than that such citizens were loyal to the Government under which they had always lived, authorized Brig.-Gen. Schofield to organize the entire militia of the State into companies, regiments, and brigades, and to order into active service such portions of the force thus organized as he might judge necessary for the purpose of putting down all marauders, and defending peaceable citizens of the State.

—The effect on the Yankee soldiers of General Pope’s recent orders to the “Army of the Rappahannock” is already being felt by the citizens of Culpeper. The party who burned the bridge over the Rapidan on the thirteenth took breakfast that morning at the house of Alexander G. Taliaferro, Colonel of the Twenty-first Virginia regiment. On their approach the Colonel was at home, and was very near being captured; but, by good management, contrived to escape. After they had breakfasted, the Yankee ruffians searched the house, took possession of the family silver, broke up the table-ware and knives and forks, eta, and actually wrenched from Mrs. Taliaferro’s finger a splendid diamond ring of great value.— Richmond Examiner, July 23.

—President Lincoln issued an order directing military commanders within the States of Virginia, North-Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas, to seize and use any property, real or personal, which might be necessary or convenient for their several commands, for supplies or for other military purposes.—(Doc. 155.)

—A band of rebel guerrillas entered Florence, Ala., and burned the warehouses containing commissary and quartermaster’s stores, and all the cotton in the vicinity. They also seized the United States steamer Colonna; and after taking all the money belonging to the vessel and passengers, they burned her. They next proceeded down the Tennessee River to Chickasaw, then to Waterloo and the vicinity of Eastport, and burned all the warehouses that contained cotton.— A band of about forty rebel guerrillas attacked a Union wagon-train near Pittsburgh Landing, Tenn., and captured sixty wagons laden with commissary and quartermaster’s stores.

—An unsuccessful effort to sink the rebel ram Arkansas, lying before Vicksburgh, was made by the Union ram Queen of the West, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel A. W. Ellet. The Arkansas was hit by the Union ram, but with very little injurious effect The fire of the rebel shore batteries was to be diverted by the gunboats under Commodore Farragut, but by some mistake they failed to do so, and the Queen of the West in making the attack was completely riddled by shot and shell from the shore batteries and the Arkansas.—(Doc. 152.)

—A party of rebel troops, who were acting as escort to the United States post surgeon at Murfreesboro, Tenn., who was returning under a flag of truce to the lines of the Union army, were fired upon when near Tazewell, Tenn., by a body of National troops belonging to General Carter’s brigade, killing and wounding several of their number.